#blessed (on Matthew 5)

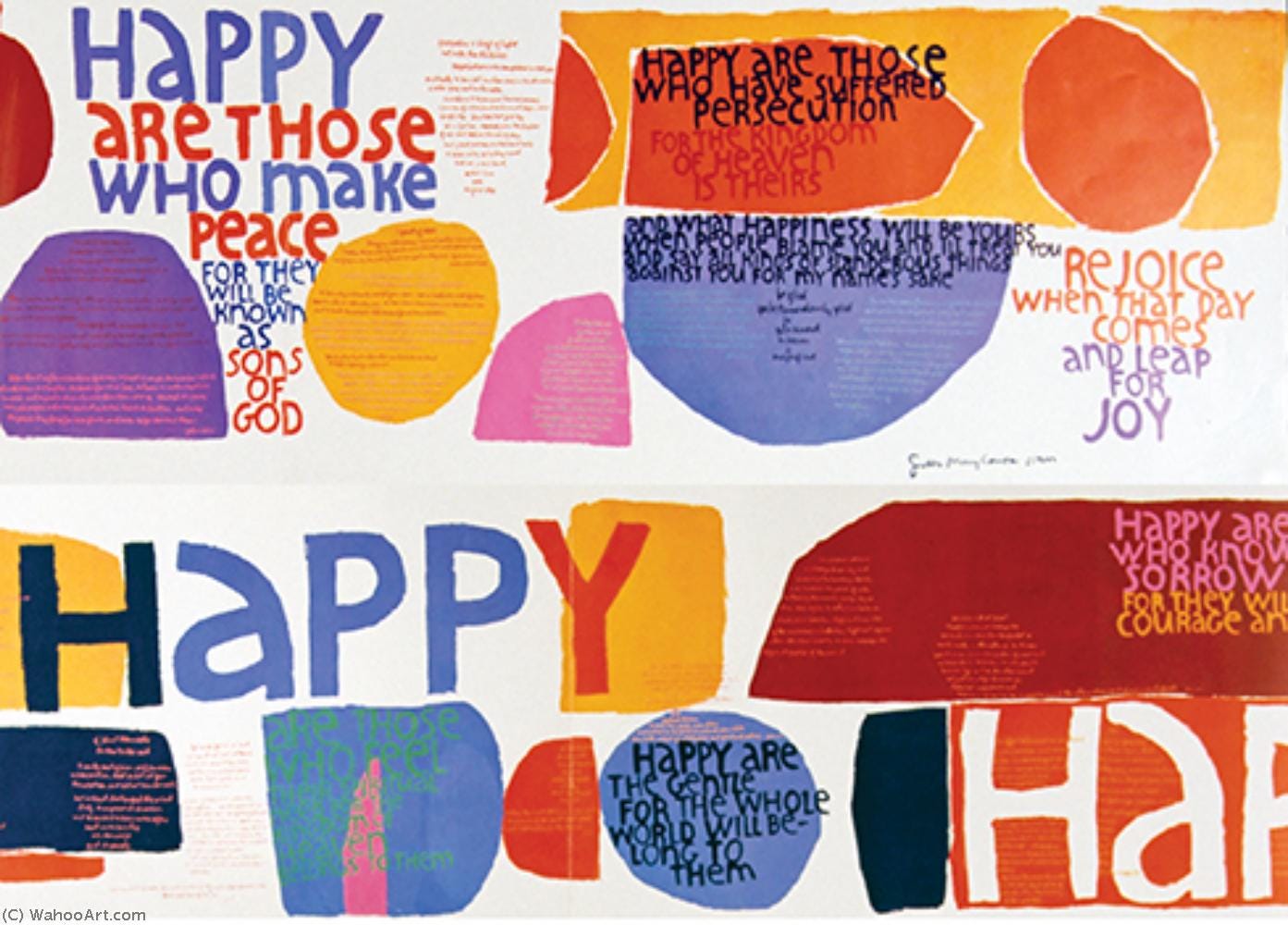

A couple of years ago, my friend Gimbiya gave me a beautiful piece of artwork that hangs now in the entryway of my apartment. The piece, by Corita Kent - also known as Sister Mary Corita - is called “Beatitudes Wall.” The artist created it as a 40-foot wall banner for the 1964 World’s Fair. I have a much smaller reproduction, but it’s still impossible to explain or experience the piece in pixels on your screen - you’ll have to come visit me and see it in person:

Corita was a contemporary of Andy Warhol and her work was important in the pop art movement. She became a nun at 18, studied art and worked for a long time as the head of the art department at Immaculate Heart College in Los Angeles. The Sisters of the Immaculate Heart were educators with progressive social teachings that got them in some very hot water with their conservative Cardinal. The order was eventually forced out of their schools and Kent left in 1968 for the East Coast, where she continued her own work until she died in 1986.

Corita’s work combined her attention to the social upheaval of the 60s and 70s with her deep spirituality. This particular piece intersperses lines from the 5th chapter of Matthew’s gospel with quotes from JFK and Pope John XXIII.

The beatitudes are the beginning of Jesus’ Sermon on the Mount, which is the bedrock of my religious tradition’s understanding of Christianity. Jesus stands up and starts preaching, and he does not start with condemnation, theological treatises or religious rules - he starts with blessing.

“Blessed are you,” Jesus says. Corita chose the translation of that phrase rendered as “Happy” in her art, and designed the work around recurrence of the term. There are other ways to understand what it means to be blessed, though: maybe it means happy, but maybe it is also a way of conferring honor. Maybe being blessed means receiving special attention or consideration. But however you translate the word, it’s clear that Jesus was doing some real work at upending both individual and societal expectations.

Blessed are the poor in spirit.

Blessed are those who mourn.

Blessed are the meek.

Blessed are those who hunger and thirst for righteousness.

Blessed are the merciful.

Blessed are the pure in heart.

Blessed are the peacemakers.

Blessed are the ones who are persecuted for righteousness.

This is mind-bending. Jesus is not giving instructions here - he is not telling us that we have to become poor or meek or hungry in order to get in good with God and achieve divine blessing. He’s not outlining an ethical process. He’s explaining that these are the people who are already blessed, beloved, chosen and accompanied by God’s own attention and care.

This is NOT how many Christians I know use the term. I hear people talk about being blessed when something good happens to them, when they’re feeling grateful or lucky or celebratory. Last night, I watched as one of the winning players of the NFC football championship started his post-game interview by ascribing the win to God.

That’s not how God works. Not only does God not give one flying fork about who wins a football championship, Jesus himself starts his longest and most detailed sermon by telling us that God’s blessing can be most easily found not among the winners but - get this - among the losers. The hungry. The mourning. The persecuted.

That, I suspect, is what got Corita and her order in trouble with the Cardinal: insisting that God’s m.o. was to bring mercy and justice, to show up among the least and the lost, to insist on what liberation theologians call a preferential option for the poor. People in power, people who assume their own blessing and privilege, don’t like to be told that God actually works in the opposite ways, that the people who are in the most direct line of blessing are probably at the bottom of our human hierarchies, not the top.

I wonder what it would be like if we used that idea of blessing in the way that Jesus did, if we could begin to think about our own lives and the lives of others in terms of the beatitudes: that we would understand ourselves as blessed and deeply beloved not when something happens to go our way or when we get a promotion or a financial windfall or feel especially confident and capable but that we would understand ourselves as blessed and deeply beloved in the moments when we are in intense mourning, when we have lost what is most precious to us, when we are hungry, when we get laid off, when we’re not sure where next month’s rent will come from, when all we have left is our own purity of heart.

And if we could understand ourselves that way - blessed and beloved, honored and worthy of care - in our own lowest moments, I wonder if we might learn how to see others the same way. I wonder if we would figure out how to honor and care for the neighbors and friends who are struggling the most, if we could recognize the poor as beloved and the meek as blessed.

I wonder how things might change if we - all of us - learned to talk about being blessed in the ways that Jesus did.

I suspect that before the world changes, a whole lot more of us will get kicked out of our religious orders, fired from our jobs, removed from the positions of power and privilege we’d been previously enjoying. I suspect that before the world changes, a whole lot more of us will become persecuted for righteousness’ sake.

And you know what? That is exactly - exactly - the place where Jesus says God’s favor rests. “Rejoice and be glad,” Jesus says, “for your reward is great.”